Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 1)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 2)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 3)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 4)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 5)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Two)

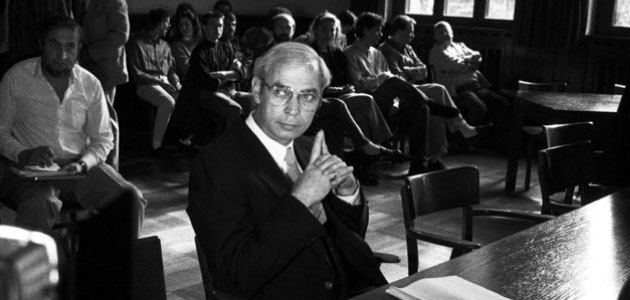

Clyde Lee Conrad on trial in a West German courtroom. Conrad was convicted on June 6, 1990

for his espionage activities while serving there on active duty in the U.S. Army,

and after he retired from the Army as a resident of West Germany

Clyde Lee Conrad on trial in a West German courtroom. Conrad was convicted on June 6, 1990

for his espionage activities while serving there on active duty in the U.S. Army,

and after he retired from the Army as a resident of West Germany

A Boston native, Roderick Ramsay was a member of the Szabo/Conrad spy ring

while stationed at the Army’s Eighth Infantry Division Headquarters in Bad Kreuznach, West Germany from 1983 to 1985, according to official accounts.

In an interview, Ramsay said his "personal involvement in the conspiracy

was from the spring of 1984 until January of 1986," when he met with the spy ring leader, Clyde Lee Conrad in his hometown where he was living at the time, Boston, MA.

Ramsay's criminal career, however, did not begin with espionage. After his arrest, in June of 1990, the Washington Post reported

that Ramsay had robbed a bankin Vermont, and that

while working as a security guard in a hospital, he had attempted to break into a safe," according to the testimony of FBI agent Joe Navarro, at his detainment

hearing the day after he was arrested on June 7, 1990.

The Vermont bank robbery took place on August 28, 1981, just eleven weeks prior to his enlisting in the Army,

and at a time when the former Northeastern University college student was living just three miles from the Gardner Museum.

In his book, Three Minutes To Doomsday, Joe Navarro recalled how Ramsay in one of his forty interviews with him in an official capacity,

had told him about the "the bank he and some pals robbed."

Ramsay lived with a high school friend in the Whittier Place building of the Charles River Park luxury apartment complex, overlooking Boston's Storrow Drive, and the Charles River

near the Boston Museum of Science.

The roommates had both attended New York Military Academy, a boarding school whose famous alumni include Donald Trump, John Gotti as well as the composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim.

Twenty four years after the robbery, on August 28, 2014, Stephen Kurkjian, author of Master Thieves, about the Gardner heist case, sent an email to Joe Navarro, at 2:44 a.m.,

which he forwarded to me, a couple of days later.

At one point in the email, Kurkjian observed that "the two roommates [Ramsay was one] look somewhat like the sketches of the two thieves."

The exchange with Navarro occurred six months before Kurkjian's book Master Thieves, came out, coinciding with the 25th anniversary of

the Gardner heist robbery. The already completed manuscript would not include anything about "the two roommates," the long time Boston Globe reporter

had made inquiries about to Navarro, in the early morning hours of his 71st birthday.

At the same time that Kurkjian's book came out, it was announced by the author and ghost writer Howard Means, that "This book still needs to be written, but

from the April 13, 2015, VARIETY: George Clooney and Grant Heslov’s Smokehouse Pictures has picked up the film rights to Joe Navarro’s “Three Minutes to Doomsday.”

That book came out two years later, but there was nothing in it linking Ramsay to the Gardner Museum, or the university he attended, the apartment complex he lived in,

or the hospital he worked at as a security guard only a short distance from the museum.

Two other friends of Ramsay, who were also recent graduates of the New York Military Academy lived nearby at Charles River Park as well. The four

friends all attended Northeastern University. With the exception of Ramsay, the four friends were from well-to-do families, the sons of successful self-employed fathers.

"I'm not like them," Ramsay would remark sometimes bitterly.

The luxury apartment complex was built on 43 acres of what had formerly been the West End, a working class neighborhood situated on prime real estate. The neighborhood was razed in 1958, displacing some 2500 families, in the name of "urban renewal." Among

those who grew up in what the government deemed a "blighted," tenement neighborhood, were actor Leonard Nimoy and the painter Hyman Bloom.

Using Ramsay's Whittier Place apartment, as a long distance staging area, three men,

two armed with shotguns, robbed the Howard Bank in Barton, Vermont,on August 28th, 1981.

A fourth man in a black,

1973 Oldsmobile

Toronado, which had been reported stolen in Massachusetts a week earlier, waited outside with the engine running. The bank was a three hour drive from Boston,

and only 22 miles from the Canadian border.

The robbers came away with about $10,000, according to news reports. Ramsay, who was only 19 years old at the time,

was said to be the mastermind of this seemingly successful robbery.

With his share of the money, Ramsay quickly left Boston. Travelling to Japan, and then to Honolulu, he enlisted in the Army in Hawaii when the money ran out.

Eighteen months later, Ramsay arrived at the military duty station that would seal his fate, the U.S. Army's Eighth Infantry Division Headquarters in Bad Kreuznach, West Germany.

was with a top secret security clearance "assigned to safeguard sensitive military plans," at what was

ground zero for "one of the largest espionage conspiracies in modern U.S. history."

In court shortly after his arrest, Navarro described the 29 year old Ramsay as a "career criminal." Yet Ramsay had managed to receive a top secret military security clearance,

when he was assigned to work under Conrad as assistant classified documents custodian of the G-3 [war] plans section.

The Szabo-Conrad spy ring was founded in 1967 by

Sergeant Zoltan Szabo, a Hungarian immigrant. The Viet Nam combat veteran and silver star recipient rose quickly through the ranks to

that of Captain, but without a college degree he lost his commission, when the war was winding down. Szabo however was given the option to reenlist

in the Army as a noncommissioned officer, a sergeant, which he did.

Sandor Kercsik told Swedish officials that in 1967 in Vienna he met an American soldier of Hungarian descent called Zoltan Szabo.

Over the next several years Dr. Kercsik delivered military secrets stolen by Mr. Szabo to the Hungarians,

according to court records in Sweden.

When Szabo lost his top-secret security clearance in 1977 for selling government-issue gasoline ration coupons on the black market, he no longer had

access to the classified documents he had been sharing with the Hungarian intelligence service.

"Still, until his retirement in 1979, Szabo personally delivered thousands of pages of classified documents stolen from under the noses of

his trusting superiors, a record that one Hungarian intelligence officer described as unequalled. But more importantly,

the inventive and resourceful operative developed into a skilled principal agent, aggressively spotting and recruiting fellow soldiers for

membership in Budapest's growing stable of disloyal Americans."

Szabo retired from the Army two years later, and moved to Austria, near the border with Hungary.

It was at this point that Clyde Lee Conrad took full control over the spy ring.

It was into this long established and ongoing espionage operation that Ramsay found himself stationed at the U.S. Army's Eighth Infantry Headquarters in Bad Kreuznach, West Germany.

Both Conrad and Ramsay worked as document custodians in the Division's G-3 [War] Plans section, with Ramsay working under Conrad both officially in his military unit,

and before long

illicitly as a member of the Conrad controlled spy ring. Conrad "is believed to have managed at least a dozen people in the U.S. Army to supply classified information.

It was one of the biggest spy rings since World War II,"

the U.S. Army Intelligence Command posted on Facebook in 2025.

Under Conrad, the operation received millions of dollars in payments from the Hungarians, nearly all of it going to Conrad himself.

The ring stole highly classified NATO and U.S. documents,

while Conrad personally negotiated their sale and arrangement for their shipment to Hungary and to a lesser extent, Czechoslovakia.

Conrad is believed to be one of only five American spies to have made more than a million dollars selling classified information to America's enemies.

But what most set both Conrad, and Ramsay

apart from other spies, was their ability to recruit fellow soldiers to work with them in their espionage activities, an extremely high risk endeavor.

"Documents provided to Hungarian agents included NATO's plans for fighting a

war against the Warsaw Pact: detailed descriptions of nuclear weapons and plans for movement of troops,

tanks and aircraft."

"In addition to disclosing NATO wartime contingency plans," the New York Times reported,

"the documents revealed key intelligence assets,

including networks and safe houses in Germany used by American intelligence agents, according to officials. The Hungarians routinely share their information with the Soviet Union."

Ramsay had been perhaps the spy ring's most prolific member, in terms of the sheer number of classified documents he managed to steal. Included in the "mother lode" of classified materials Ramsay

passed over to Conrad, many of which he recorded with a video camera,

were documents on the use of tactical nuclear weapons by US and NATO forces,

strategic plans for the defense of Europe in the event of an attack by Soviet and Warsaw Pact military forces, and manuals on military communications technology.

After ten plus years of the spy ring’s successful operation, however,

a senior member of the Hungarian Intelligence, Lt. Col. István Belovai, alerted the CIA

that a huge number of classified U.S. and NATO documents were being passed to Hungary, from somewhere inside West Germany.

But before the Army's investigation was completed, Belovai, who had come under suspicion by Hungarian counterintelligence services, was arrested making a pickup at a CIA drop in Hungary in 1985.

He believed he was a victim of CIA double agent Aldrich Ames.

But by the time of his arrest, Belovai had already provided a list of specific classified documents, which he knew to have been shared with Hungarian intelligence.

This list

enabled the Army to narrow their focus of their investigation to the soldiers, who would have had access to the specific documents on the list.

After a massive investigation, the Army managed to identify and prosecute most of the members of the spy ring. In the case of Clyde Lee Conrad however,

the U.S. Army worked through the civilian judicial system of West Germany where Conrad then resided.

The fact that there was no extradition treaty between the U.S. and West Germany for the crime of espionage was the explanation given for why the U.S. Army worked

through West German authorities to prosecute Conrad. As a military retiree, however, Conrad could have been brought back onto active duty and court martialed.

The FBI first interviewed Ramsay about security breaches at the Army Eighth Infantry Headquarters

on August 23, 1988. Almost three years after he had been honorably discharged from the U.S. Army. Over 40 additional interviews

of Ramsay by the FBI until Ramsay's arrest in June of 1990, and many after his arrest would follow.

That first meeting between Ramsay and federal investigators took place only hours after Conrad's arrest

at his home in Bosenheim, West Germany. Picking the lock on Conrad's front door at dawn, German police quietly entered

Conrad's bedroom with guns drawn. Police confronted the master spy while he was still in bed with his wife.

"You vill take ze hands out of ze vife and place zem vere vee can

see zem," a German police investigator, Holger Klein, ordered Conrad, in broken English.

"The day of reckoning Conrad had feared for over two years had arrived," Stuart

Herrington wrote in his book, Traitors Among Us: Inside the Spy Catcher's World.

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Three)

|

By Kerry Joyce