|

The Gardner Museum's Disinforming Ad Campaign (Part One)

Link to (Part Two)

For over a month at least now, the Gardner Museum has been running Google paid search ads with keywords regarding the Gardner heist, covering an area at least 50 miles from the museum and out of state. Last month, for example, I entered: [gardner rick abath] into Google, and my search results included an ad for the Gardner Museum.

The landing page for the ad was a page on the Gardner Museum website with the header "Gardner Museum Theft: An Active and Ongoing Investigation."

Gardner Museum "Heist" Ad June 22, 2025

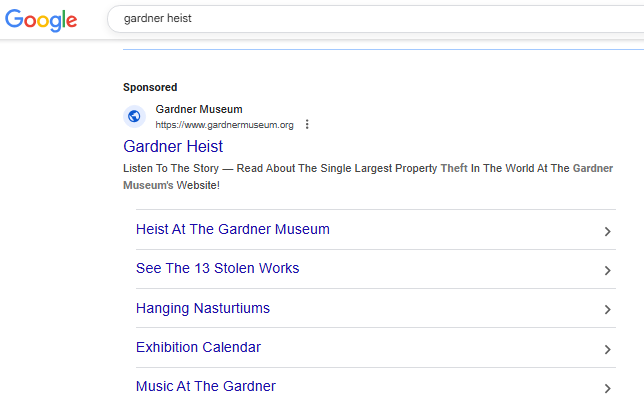

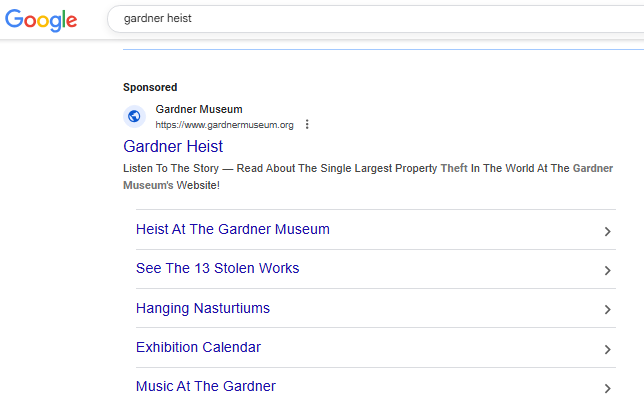

Frequently, the Gardner Museum runs what google calls half-page ads, and even two ads

on the same page in google-keyword search results. These ads are probably inexpensive, since Google ad prices are based on an auction system, and no

one else is buying ads for the keywords [gardner heist].

But the Gardner Museum is spending some money to bring people to a particular page on their website about the robbery.

What is the point, exactly? The Gardner Museum's

"theft" page is consistently at or near the top of Google natural search results for "Gardner heist," for free, in repsonse to

a query on google to [gardner heist] and the Google algorithm. So if you were to put [gardner heist] into Google, you stand a chance of Google returning results

with three of the top ten results being the Gardner Museum. What other crime victim dominates the search results

on their own victimization in this way? Has the media coverage of this widely reported crime so weak that the museum's coverage

takes such overwhelming precedence?

Without

scrolling, the only thing displayed on the museum's landing page, which you arrive at if you click on the ad,

is a large photograph of the Gardner Museum Dutch Room. Then, further down is some dodgy history

about the theft, and finally, some pictures of the stolen art at the bottom of the page.

The ad itself has some false information in it, too. The headline includes: "See The 13 Stolen Works."

Apparently, the Gardner Museum assumes that everyone knows that none of the art has been recovered,

and that you can't see any of it. All you can see are photographs of the stolen items on this webpage, which is not the same thing.

There is nothing special about the photographs. These same images can be found in a lot

of places.

The ad also invites visitors to retrace the steps of the thieves. This, too, is false. There was no equipment in the

Gardner Museum at that time that recorded the steps of the thieves, or movement of any kind, most importantly

within any gallery.

Further down on the webpage, the Museum asserts that

"the facts are these: In the early hours of March 18, 1990, two men in police uniforms rang the Museum intercom and stated

they were responding to a disturbance.

This is not a fact. This is an uncorroborated and

updated account of what happened, taken from Rick Abath, the security guard who let the two thieves in. There are no witnesses

to what Abath claims were the words exchanged between him and the thieves he allowed in, except for the thieves themselves,

and The Boston Globe reported in March of 2025 that the Gardner

heist's own lead investigator for the previous 22 years, Geoff Kelly, is "convinced" that Abath was one of the Gardner heist thieves.

Abath is hardly someone whose statements can be accepted as "the facts."

In addition, Abath was initially interviewed by the Boston Police, and in their official report, it states that Abath told them that the

two fake cops said they were responding to the kids in the street after they were permitted inside the building.

He did not claim that the cops said they were responding to a disturbance until years later.

Next, the Museum says that "the guard on duty broke protocol and allowed them through the employee entrance."

Saying that he broke protocol suggests that breaking protocol was all Abath had done. If he was one of the thieves, which Kelly now says he is convinced is the case, then he didn't just break protocol;

he broke the law, and all this discussion of whether he was trained not to let anyone in, even cops, is moot.

"At the thieves’ direction, he stepped away from the security desk," the Gardner reports, but again, this

is the uncorroborated account of someone who is considered one of the perpetrators. There is no electronic footprint

of Abath's and the other thieves' actions and interactions.

"He and a second security guard were led to the basement of the Museum where they were restrained." More specifically,

he and the other guard

were led to the basement after Abath called the other guard on a radio and asked him to return to the security station, without telling him the reason.

This second guard was handcuffed and blindfolded with duct tape before being brought down to the basement, but we have only

Abath's questionable word that he too was led to the basement and restrained, since the other guard was unable to see.

They cut Rembrandt’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee and A Lady and Gentleman in Black from their frames.

These two Rembrandt works were not cut from their frames. They were cut from their stretchers, which preserves more of the painting intact and

explains why they broke the frames.

Thomas Cassano, when he was the FBI's Supervisory Special Agent for the Gardner case, said that "the first two paintings

stolen were damaged. Rembrandt’s “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee” and “A Lady and Gentleman in Black”

were both taken from the wall, their frames smashed, and the canvases cut from their stretchers," Antiques and the Arts reported

in November of 2000.

Ten years later, Anthony Amore, security director for the Gardner Museum, said that

"they took a very sharp instrument we can tell by the grooves left in the stretchers," Amore

in an interview in 2010. If the paintings were cut from their frames, there would be deep grooves left by the thieves in the frames, not in the stretchers.

The fact that the thieves took the extra step, in the heat of a robbery, to cut the paintings from their stretchers instead of the

frames suggests, "How they went about removing the paintings – slicing them from their frames – that's indicative of a rank amateur when it comes to art theft," Kelly said in 2013.

But that fits the profile of the kind of individual the FBI was interested in pinning the robbery on, while not what actually happened

in fact.

Next, the Gardner's version of what happened during the robbery claims:

"Motion detectors recorded the thieves’ movements as they made their way to the galleries," the webpage states.

Also not true. There

were no motion detectors inside the Gardner Museum at that time. The only information the Gardner Museum's security

system recorded were the entrance and exit of anyone going into the galleries and other sectors of the museum thanks to

"electric eyes" installed in the door jambs.

An electric eye is a type of sensor that detects the presence of an object by interrupting a light beam, while

a motion sensor detects movement within a specific area. The only movements recorded were that of the thieves

entering and exiting galleries and other sections of the museum.

The Museum also states here that these same two men "also stole Manet’s Chez Tortoni from the Blue Room

on the Museum’s first floor, leaving its frame behind as well," but the FBI's former lead investigator, Geoff Kelly, told The Boston

Globe he believes it was Rick Abath who removed the Manet from the Blue Room, not the two thieves Abath

had let in that night. So again, not one of "the facts," if the FBI's lead investigator is contradicting it. Rick Abath died in 2024,

and whatever secrets he had left, he took with him, and that was when the narrative started to change about Rick Abath.

"The thieves departed at 2:45 am, making two separate trips to their car with the artworks."

This is not a fact. All that is known is that the door opened at 2:41 and again at 2:45, and it is speculated that is when the thieves

left with the stolen art. "We know how they came in, but we don’t know how they got out,”

Thomas Cassano, Supervisory Special Agent for the Gardner case at the time of the theft and for over ten years afterward,

said in 2015. If they don't know how they got out, then it is not an established fact that they left through the door at 2:45.

The information on the page concludes: "The guards remained handcuffed until police arrived at 8:15 am."

But a closeup of Abath's wrist in a crime scene photo shown on the Netflix documentary "This Is A Robbery" clearly shows that

Abath's hands were not handcuffed. John Green, the FBI Forensic Photographer, who was on the scene that day, said: "His [Abath's]

hands were bound, which I thought was kind of odd. They had a little pad," he said, referring to what appears to be a squishy foam

pad between Abath's wrists.

In the seven-plus hours from when the thieves brought Abath to the basement and when the Boston Police photos were

taken, there is no discernible sign of sweating or struggling. Abath’s clothing, and particularly

the duct tape, appear fresh and smooth in the crime scene photograph. There is no sign of stretching

or wear on the duct tape around his ankles, and his demeanor overall as shown in the photographs, as well

as the fact that he drove to Hartford to attend a Grateful Dead concert that night and again the following

night, suggests that Abath had not been tied up for over seven hours in the basement of the Gardner Museum. There is nothing

in the photos that would look any more out of place than if Abath had been tied up for seven minutes instead of seven hours.

And given the fact that the retired lead investigator on the case now says he is convinced that Abath was involved, it seems

unlikely that he would be tied up for over seven hours when he could serve as a lookout or respond to anything unexpected, or

would just not be willing to voluntarily be restrained for several hours.

In addition, the guards were not released when the police arrived. The police started searching the museum on the fourth floor and worked

their way down to the basement after searching the other four floors. Over an hour had passed by the time they reached Abath,

who did not call out, even though the duct tape was around his mouth and not over it, and there was nothing to prevent him from hollering his head off.

The webpage has a link to an "immersive" audio walk, where visitors to the webpage or the museum can

"retrace the steps of the thieves with Anthony Amore, Director of Security." There is also a link

to a written transcript of the audio walk. This audio walk packs in quite a lot of deceptively false facts as well.

Continue to Part 2

Gardner Museum "Heist" Ad August 20, 2025

|