|

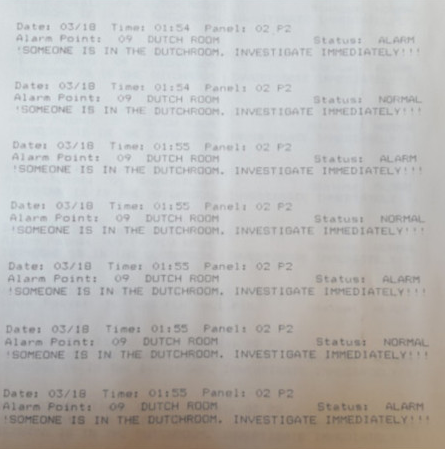

PART 2 False Facts In The Gardner Museum Audio WalkText taken directly from the Audio Walk appear in blue. Amore: Thank you for joining me [Gardner Museum Security Direct Anthony Amore] as we retrace the thieves’ steps—and find out what really happened—on March 18th, 1990.This museum audio description of the Gardner heist does not describe "what really happened." There are numerous false facts, and unsubstantiated claims presented as facts, which showcase the museum's willingness to support the FBI's disinforming false narrative about the Gardner heist, which seeks to explain the Gardner heist case as "the handiwork of a bumbling confederation of Boston gangsters and out-of-state Mafia middlemen, many now long dead," while protecting Abath so long as he kept his mouth shut. Silencing Abath had formerly been a top priority for the FBI, until he died in 2024. Now after twenty years of claiming that Abath was not a suspect, the Boston Globe is reporting that the former Gardner heist lead investigator, Geoff Kelly is convinced that Abath was involved. The museum audio also glosses over the utter lack of any tangible basis for concluding there had ever been any actual investigation of the Gardner heist, as the term is generally understood, or anything other than the blocking of an investigation into what actually happened, by the FBI. Let's begin. There was no equipment in the Gardner Museum in 1990 that could retrace the thieves' steps. There were electric eyes in the door jambs of the galleries, which recorded when someone entered or exited some of the galleries and other spaces in the museum. This could be chalked up to a metaphorical description, but it has been repeated so many times over 15 years that it gives an added measure of knowledge, and authority to what is known and being shared with the public. Most people who have spent time learning about the case are surprised to learn that there was no equipment literally tracking the steps of the thieves. At no time has anyone involved in the investigation made any reference to the electric eyes in the door jambs, in speaking publicly about the case. In 2009 the Boston Herald reported, "The thieves shut off a printer that spit out line-by-line data on any alarms that would be triggered by movements in the museum. But the computer hard drive still recorded their footsteps in the galleries." No equipment "recorded their footsteps." Amore: Two security guards were on overnight duty, as was typical. They’re stationed at a security area downstairs.In this case where the security guards were "stationed," and where they were in fact located were two distinctly different things, when the thieves entered the building. One of the guards was indeed located in the security station. He alone made the decision to let the thieves into the building. At some point later, that guard called the other guard on a walkie talkie, and asked him to return to the security station, he says, as he had been instructed to do by one of the thieves. "Inside the Venetian-palace-style building, two young watchmen were on duty. One of the security men was seated at a guard’s desk in an office next to a door facing the Palace Road side entry. The second guard was doing lengthy rounds within the compound," the Boston Herald reported in 2009. The guard was only ten seconds away on the stairs near the security station, when he was called by the guard inside the security station, Rick Abath. Amore: The thieves had presented themselves at the locked outside door to that security area at 1:24 am - dressed as Boston police officers. We have only Rick Abath's word that the thieves came to the door at 1:24 a.m. The door was also opened at 1:04 a.m., when Rick Abath was alone in the security station. Abath claims he was checking to make sure the door was securely locked, when he opened it at 1:04 a.m. but one of his supervisors J.P. Kroger, told me that the guard were equipped with an electronic wand, which the guards could use to ascertain if the door was securely locked without the need to open it. A review of Abath's activity on other nights did not record him opening the door to test the door, like he "always did," as he claimed. Abath is lying about the circumstances surrounding his opening the door, at least once and therefore he is not credible for either time that he opened the door. The thieves were not dressed as Boston Police officers. The overcoats they wore were not part of the Boston Police uniform. One witness had said that at least one of the thieves had a Boston Police shoulder patch on his coat. On the day of the robbery Boston Police spokesman, Captain David Walsh, said that "a couple of individuals dressed in security guard or police uniforms not in the uniform of the Boston Police, ostensibly identified themselves as Boston Police officers investigating a disturbance around the building." Somewhere along the way, the ostensibly part of the heist narrative introduced by Captain Walsh was dropped, while the information implicating Abath continued to grow. Amore: Over the intercom from outside, the thieves say that they’re responding to a report of a disturbance. It seemed plausible. After all, it was the night of St. Patrick’s Day. Revelers are still out on the streets. Against protocol, the thieves disguised as police are buzzed in. "It seemed plausible." Amore uses the past tense here. He is taking Abath's part in describing Abath's thinking. Eye witnesses said it was quiet on Palace Rd. Most of the property in the area is educational institutions. The nearest bar was a half mile away on the other side of Huntington Avenue. The big city-wide observation of Saint Patrick's Day was not until the next day, the day of the South Boston St. Patrick's Day breakfast. Most of the state's leading elected office holders and candidates would attend and this was followed by the South Boston St. Patrick's Day parade.As stated previously, Abath was initially interviewed by the Boston Police, and in their official report, it states that Abath told them that the two thieves said they were responding to the kids in the street after they were permitted inside the building. Amore: Against protocol, the thieves disguised as police are buzzed in. The passive voice here, "the thieves...are buzzed in," despersonalizes a key act in the commission of the Gardner heist." "Amore has referred to it as the biggest mistake in the history of property protection." Who made this mistake? "I'm the guy who opened up the door. They're obviously going to be looking at me." Rick Abath said in 2013, when he was interviewed by CNN. And according to the FBI's retired lead investigator, on the case for over two decades, Geoff Kelly, that decision was more than just against protocol, it was a willful, criminal act. Amore: Once inside, they immediately overtake the security guards... They did not immediately overtake the guards. One of the guards was not even present. "Within two minutes, the thieves had placed the inexperienced guards 'under arrest,'" the Boston Herald reported in 2009, which also stated that "a timeline of the crooks’ movements was provided to the Herald by museum Security Director Anthony M. Amore."Rick Abath told CNN that: "One of them came right over to my desk. And one of them kind of stood in the alcove right there, just looking around, which didn't seem particularly odd to me. And he came up to me, the one guy, and they asked me -- he asked me if I was alone. And I said that, no, my partner was off doing a round. He said, get him down here. So, I called him on the radio." Amore: Cover their eyes and mouths with duct tape... Abath's eyes were not completely covered. The tape was wrapped around Abath's head, under his eyebrows, and under his ears. One of Abath's eyes, uncovered, is plainly visible in a crime scene photo shown in the 2021 Netflix documentary, This Is a Robbery. In addition, Abath said in 2013 on CNN that "I could see a little bit over the duct tape, kind of. And at one point, somebody did come and check on me," Also, Abath's mouth was not covered with duct tape. It was 24 minutes from the time Amore says the thieves first entered the building and the time they entered the Dutch Room. It would not take 24 minutes to secure the thieves in the basement, so they did not go directly to the Dutch Room. We believe that the point of the theft was to get works by the Dutch artist, Rembrandt. In fact, every other museum in Massachusetts with Rembrandt paintings had been robbed before us. The empty frame on the wall opposite the doorway held the only seascape Rembrandt ever painted. Vermeer's "The Concert," also stolen that night, is far more valuable than the Rembrandts and all of the other art and paintings stolen that night combined, by over $100 million dollars. Amore does not specify who is meant by "we," but it is certainly open for discussion, when the most valuable item taken is not considered the target. Overall, a lot of the information in the Audio Tour draws conclusions, based on conjecture, or little information, which invariably fits the narrative (profile) of the thieves not knowing what they are doing. This is just one of several examples. Amore: The thieves take the painting down off the wall. They put it on the floor near this wall, face up. The motion sensors show us the path the thieves took that night. That’s the route we’re following. There were NO motion sensors. There are electric eyes in door jambs of the galleries. There is no electronic record of where the thieves were positioned, during the time they were inside the Dutch Room, or in any other gallery. If Amore has decided that the thieves "put it on the floor near this wall," his conclusion is not based on any "motion sensor" data. Aside from video cameras, the museum security system only recorded when the thieves, or others after hours, came into the Dutch and and when they left the Dutch Room. Amore: The sound you’re hearing now is the type of computer printer in 1990—a dot matrix printer. On their way out of the Museum, the thieves take the dot matrix printout tracking their movements with them. But they didn’t realize that to get another copy, all we had to do was to hit the ‘print’ button again. In 1990, technology wasn’t part of the thieves’s planning. It would take one of the thieves two seconds to remove a printout and stuff it in his pocket. There could be other motivations for taking the printer than to permanently destroy a record of their activities. There was little reason to care if investigators knew when they had been in which gallery, in any case. The most incriminating piece of evidence from the computer printout was that Abath was the only one who had been in the Blue Room after midnight, and Abath certainly understood the workings of the motion detector system. On an episode of CNN's How It Really Happened,Abath can be heard saying from an old interview he did with Stephen Kurkjian that: "There were motion detectors and so while one person was walking through the museum, they would be setting off the motion detector alarms.

Amore: It wasn’t until a day after the theft—when conservators were in this space,

cleaning up the broken glass from the drawings—that they discovered that something

else was missing. In the corner where the fire extinguisher is now, there was a bucket of

sand, for fire suppression—and in that bucket the conservators find the screws from the

flag’s frame.

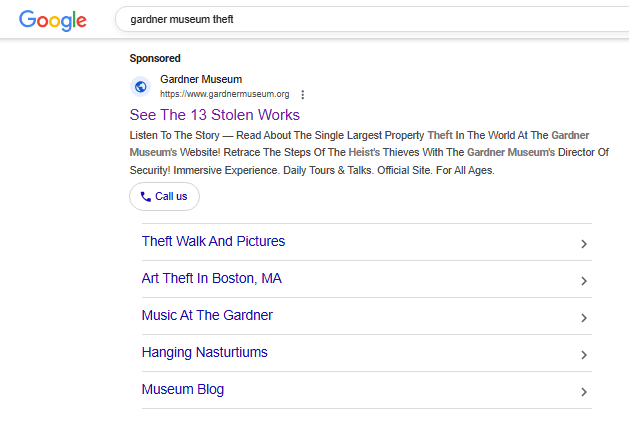

On March 21st, the Boston Globe reported that "museum director Anne Hawley told reporters that an inventory yesterday, [March 20th, two days after the Gardner heist] showed that a gilded bronze eagle finial was also taken by two thieves." So Kurkjian has it right that it was two days not one, and it seems more likely that the thieves, working in the dark, would be more inclined to throw the screws to the floor than to hold onto them and then place them into the bucket of sand. It seems more likely that a janitor vacuumed them up than that conservators were looking into the bucket of sand as well. The Museum audio version also does not address the issue of the FBI overlooking key pieces of evidence, from which a DNA sample could possibly have been taken, for that matter, neither does Kurkjian. Amore: The thieves go out the security entrance from which they entered. It used to be in an area not far from where you came down the stairs. Separately, they make two trips to load the stolen works into their vehicle. By this time, it’s 2:45 a.m. The thieves may well have come in at 1:04 a.m. since Abath's explanation of why he opened the door at that time does not hold water. Some have suggested Abath opened the door as a signal, but all of the guards were equipped with extra large flashlights, and the Museum has numerous windows. There would be no reason to open the door simply to send a visual signal. There are no witnesses to substantiate the claim that the thieves left at 2:45 a.m. All that is known is that the doors were opened and closed at 2:41 a.m. and 2:45 a.m. In 2016, former Gardner heist investigation supervisor Tom Cassano said: "We know how they came in, but we don’t know how they got out.” Amore: Before they leave there’s one more artwork they take with them. But we don’t know when they took this one—because the motion sensors don’t pick up their movements into or within the room it’s in. The former FBI's lead investigator, Geoff Kelly told the Boston Globe in March of 2025 that he is "convinced" the security guard Rick Abath took the Manet from the Blue Room. And in 2015 Kelly said on CBS Good Morning that: "Someone went into the Blue Room that night, and the only one that went in that room that night was the security guard [Rick Abath], according to the motion sensor printouts." Amore: please contact us at Theft@GardnerMuseum.org if you have any concrete information. Any facts. And not theories. Believe me, we’ve heard all the theories a thousand times. The museum has not heard the right theory or they would have their art back, or at least know what happened to it. Theories are an essential component of discovery, as is community engagement, in a case such as the Gardner heist. One theory is that Amore's unwillingness to engage with people about theories, suggests he is trying to hide something. There is no other criminal case where someone purporting to be an investigator tries to limit the discussion in this way. When pressed, Amore blames the public, when it comes to naming the suspects for example, for the unique nature of the Gardner heist investigation. "We believe it's a much more effective way to investigate it via going to people we know who are connected to those [names] instead of putting these names out there and getting flooded and I mean flooded with calls, not just from psychics and what have you, but from con men and theorists."Geoff Kelly, whom Amore claims he still speaks with every day about the case, named the people they want you to think did it in the Boston Globe in March of 2025, after hinting the names for ten years, and the museum, and the sanctity of this going nowhere investigation continues apace, going exactly where it has been heading for 35 years, nowhere. But now Amore has changed his position again. "I don't really care who took them," he said in March. "I just want to know where are they sitting right now, so I can go and get them, which if he actually did do that he would be guilty of a felony punishable by up to ten years in prison: 2) knowing that an object of cultural heritage has been stolen or obtained by fraud, if in fact the object was stolen or obtained from the care, custody, or control of a museum (whether or not that fact is known to the person), receives, conceals, exhibits, or disposes of the object, shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both. These days Amore sounds more like he is willing to hear more theories. Amore: "I try not to get into individual names, because I don't want to inhibit anyone in the public who might know something different. I worry that someone will hear me say a name or two and say, 'Oh I must be wrong.' and then never tell me. So there are people who mention names, which is fine, but I like to keep it open. for the public to come forward to me and tell me what they know."So the Gardner Museum, through google paid search advertising, continues to pay money to send people to web pages that are so obsolete, they are not even consistent with their own updated, insincere messaging about the case. Seven years ago Amore said on GBH's Greater Boston that he knows who did it. Now he says he doesn't "really care who took them."The Gardner heist is a crime with billion victims. As the museum likes to remind us, these stolen works are important pieces of our civilization. The Museum on its website suggests that Rick Abath was tricked, that he was not a party to the robbery. The former lead investigator, Geoff Kelly, however, now says Abath was one of thieves. Amore, the Museum's spokesperson, the guy who narrates the museum's audio tour of the theft, doesn't care who did it.In 2006, Whitey Bulger prosecutor Fred Wyshak said: "The system is served not only when people go to jail, but also when the wrongdoing is brought to light so the public can see it." The public may not have a right to know, but they have a right to want to know, and that should not be encumbered by the principal victim of the Gardner heist, who is not the only crime victim, as they try to draw in more visitors through their victimization with paid google ads, specifically targeting to those interested in the Gardner heist, not necessarily looking for a place to spend the afternoon. Gardner Museum google ad from August 13, 2025

Gardner Museum google ad from August 13, 2025 |

Copyright © 2025 All Rights Reserved kerry@gardnerheist.com