Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 1)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 2)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 3)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 4)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 5)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Four)

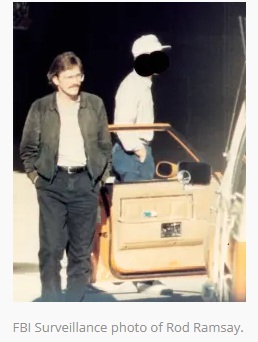

For twenty months, after having implicated himself in espionage, Ramsay had been free to come and go as he pleased.

There was not even any surveillance on him of any kind for over a year, or so Navarro stated in his book:

For a year Ramsay was seemingly left to his own devices to try to develop a plan to extricate himself from this seemingly hopeless predicament.

Perhaps counter intelligence operatives were interested in what Ramsay would do in such a desperate situation, and sought to find out whom he would contact, by keeping him

under surveillance, but in secret, even from agent Navarro.

In a scene in the fictional TV series The Americans, a Russian spy character named Nina Krilova, remarked to one of the FBI's spy-catchers in an episode:

“What do you want with us? With Arkady and the others at the Rezidentura? Do you want to put them in jail? That's how policeman thinks, not how spies think.

We want everyone to stay right where they are, and bleed everything they know out of them forever.”

So it might well have been with Ramsay. The FBI’s desire to gather information from him, including information he would not readily

give up voluntarily was a higher priority than prosecuting him for espionage, especially at the beginning of their engagement with him.

About a month after the start of Agent Navarro's second round of meetings with Ramsay,

ABC News reported on October 30th, 1989, that Conrad’s recruits continued to work for him back in the United States,

illegally exporting hundreds of thousands of

advanced computer chips to the Eastern Bloc, through a dummy company in Canada.

Ramsay admitted to the FBI that he was the source of that ABC News story, but said that he and Conrad had only discussed illegally exporting chips to the Eastern Bloc, during

their brief meeting in Boston, in January of 1986, but the

project, Ramsay claimed, had never gotten off the ground.

The two spies

had never followed through on their plan to illegally export the computer chips, he insisted. “That [ABC] producer, Jim Bamford, he kept bothering my mother. She was getting very

upset. I thought if I just gave him this one little story, some bullshit, he would go away,” Ramsay told Navarro.

In that way Ramsay acknowledged that he and Conrad had at least engaged in the planning stages of illegal acts inside the United States

that threatened national security.

Facing the possibility of decades in prison, or even life, Ramsay was an individual in desperate circumstances, but one with a sharp and experienced criminal mind

with which to come up with the means to possibly save himself.

The only alternative to abjectly submitting to his fate in the federal criminal justice system, with the weak cards he was holding, would have been

to come up with some different cards, a plan, something big, given the kind of manhunt that he, as one of the most prolific spies in American history would be up against, if he simply

fled.

Ramsay would need a caper big enough to make such a manhunt something that could be either overcome or unnecessary, a plan where he would be negotiating from strength and could strike some kind of a deal. At the very least it would have to be able to help make his life more comfortable while he was inside prison, and perhaps after he got out, with a shorter sentence possibly, as well.

"Over 25 years, so many names have been thrown into this [the Gardner heist case],"

Kurkjian said in 2015. But none of those so many names included Rod Ramsay, and none had the kind of motivation, the desperation, or the kind of extensive criminal background that

Ramsay had, which matched up so well with pulling off the Gardner heist. Nor did any of those "so many names," like Ramsay's, have the need for secrecy that

the government might deem necessary, if it were a spy who robbed the Gardner, and not some local hood, whom the FBI never quite got around to interviewing.

Unlike all of the other members of his espionage gang, Clyde Lee Conrad was not cooperating with investigators in any way, and never did. The master spy who recruited Ramsay and others, earning for himself millions of dollars from America’s enemies, died in prison, less than ten years later, without having admitted to any wrongdoing. Denying all of the charges against him, Conrad did not implicate Ramsay or anyone else, in acts of espionage after his arrest.

Ramsay may have had buyer’s remorse. He might not have liked the weak negotiating position he found himself in with the people investigating the spy ring, and may have wanted to do something to help his friend Clyde Lee Conrad and himself.

There is indeed strong evidence, not shared directly with the public, pointing to the art having been taken as a get-out-of-jail-free card. In 1976,

Myles Connor had famously arranged for the return of a Rembrandt stolen from the Museum of Fine Arts, in Ramsay's hometown of Boston, MA.

in exchange for a reduced sentence. In addition, a very close associate of

Ramsay's was from Connor's hometown of Milton, Massachusetts, although the friend, a former boarding room classmate, and college friend, was twenty years younger than Connor.

The association added to the possibility that Ramsay was familiar with the story of how Connor had made a

deal for a shorter sentence, by returning a Rembrandt painting, "Portrait of a Girl Wearing a Gold-Trimmed Cloak”

Connor would later claim starting over three decades later,

that he had himself stolen the work although

his various and wildly divergent accounts, to authors and journalists as cravenly hungry for attention and celebrity as Connor himself, as well as the fact that he did not fit the description

of the robber put out by the police, suggests otherwise. More likely Connor was "Myles away," at the time of the robbery

as his former friend William Youngworth put it. But Connor was nonetheless able to negotiate the return of the painting from the Charles Street jail.

Four years after the heist, the Gardner museum director Anne Hawley received a ransom note, and a follow up letter. According to Stephen Kurkjian in his book Master Thieves,

"the letter writer stated that the paintings had been stolen to gain someone a reduction in a prison sentence, but as that opportunity had dwindled dramatically there was no longer

a primary motive for keeping the artwork." The most likely reason for putting this bit of backstory into the ransom note would have been to establish credibility,

since if no offer had ever been previously made to negotiate on these terms, for a reduction in prison sentence, then

that statement would call into question the authenticity of the ransom note.

Fourteen years after receiving the notes, the FBI still had not ruled out the possibility that the ransom notes were

indeed legitimate. "In 1994 we took it [the ransom notes] very seriously and we continue to take it very seriously," the FBI's Gardner heist lead investigator

Geoff Kelly said on a segment of American Greed in 2008, called Unsolved: $300 Million Art Heist.

Gardner Museum director Anne Hawley, also felt there was reason to believe the ransom note was real. In a CNN segment about the Gardner heist in 2005, there was

"an exclusive on camera appeal from the museum's director, an overture to an anonymous

letter writer eleven years ago who seemed legitimate."

Hawley: "I'm particularly interested in hearing from that person who had, I think, a real concern about our getting the work back."

In 2015, Hawley said on CBS Good Morning, "When people say, 'Well, why is it important?' I say, 'Imagine if you could never hear Beethoven's Seventh Symphony again, ever,'" Hawley said on CBS Good Morning in 2105, adding

"a Vermeer is certainly at that level of creation, and so is the 'Storm of the Sea of Galilee."

The Gardner heist, therefore, is a crime with a multitude of victims, millions of people have experienced a sense of loss from these missing works. But millions of people

were the victims of Ramsay's espionage as well. Ramsay was already living in a kind of exile on Main Street, dwelling in a state of anticipated estrangement from his fellow citizens, when

news of his spying was released to the public. Tens of millions of art lovers was not going to change the state of his relationship to society at large.

Hawley supplied other information that suggests the Gardner heist thieves were not ordinary street criminals as well. In 2013, twenty three years after the heist, and

ten weeks after I had first contacted the Gardner Museum

about my speculation that Rod Ramsay may have been one of the Gardner thieves, Anne Hawley told a WBUR reporter that

"The museum was experiencing these bomb threats coming from people in penitentiaries that were trying to negotiate with the FBI on information they said they had — and the FBI wasn’t

responding to them so they were hitting us. You can’t paint a more difficult time." If the Gardner heist investigation was being handled as a standard

robbery investigation and not something more, as part of a counter intelligence operation,

they would have spoken to this person who was so desperate to speak with them, they were committing additional crimes from behind bars, which could easily

be traced back to them, just to speak with them.

Six weeks later, in 2013, Hawley reiterated those claims in an interview she did on the WGBH news program Greater Boston. “We also were being threatened from the outside by criminals

who want attention from the FBI, and so they were threatening us, and threatening putting bombs in the museum,” Anne

Hawley said recently. “We were evacuating the museum, the

staff members were under threat, no one really knew what

kind of a cauldron we were in.”

The head of the museum claimed there were "criminals who wanted attention from the FBI," but this story and the ordeal the Museum underwent was not reported until 23 years later, and

no other news media ever picked up on the story either time.

"In an interview with Hawley when she retired in 2015, the Boston Globe described the dangers Hawley felt at that time.

Hawley endured death threats in the months immediately following the robbery.

She twice evacuated the museum after bomb scares, and the FBI instructed her to take a different route home each night from work."

“'They scared me,' said Hawley. 'I wouldn’t go out of my house alone at night,'” but the Boston Globe reporter Malcolm Gay, left out a critical

part of the story, the WHY, Hawley and the Gardner Museum were the target of bomb threats. It was because there was someone who wanted to

speak with the FBI about the case, and the FBI would not speak with them, as was stated by Hawley on two different occasions to two different media outlets.

"The FBI has searched basements and attics, conducted elaborate sting operations from Miami to Marseilles, and tracked thousands of leads in the United States,

Japan, England, Ireland, Russia, Canada, and Spain."

“If these paintings do not get recovered — and I hope that’s not the case — it’s not going to be for lack of trying by the FBI, the museum, and the US attorney’s office,"

said FBI special agent Geoff Kelly, who has spearheaded the investigation for a dozen years."

Yet the history of the investigation that can be documented and corroborated suggests otherwise," with people who claimed to have information including eyewitnesses, saying they were

met with indifference, rudeness, intimidation, or never followed up with at all.

The sting operations from Miami to Marseille, refers to any undercover operation conducted by Robert Wittman. The New York Times reported:

"Mr. Wittman wrote that his efforts in the investigation, called Operation Masterpiece, were sabotaged by an F.B.I. superior, called “Fred”

in the book, who micromanaged his work and tried to get him thrown off the case. 'We’d blown an opportunity to infiltrate a major art crime ring in France,

a loose network of mobsters holding as many as 70 stolen masterpieces,' Mr. Wittman wrote."

There is some evidence of an effort to recover the art, somewhat diminished by ridiculous, uncorroborated claims,

however, the already challenging proposition of recovering the stolen Gardner art, is clearly subordinated to two higher priorities. The first is that

the government will not reveal the identities of the original Gardner heist thieves, which is a hindrance to the recovery.

The government, for example, was willing to publicly conclude that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the authoritarian ruler of Saudi Arabia,

a sometimes vitally important strategic partner of the United States,

"approved the gruesome political killing of Jamal Khashoggi,"

in the year following his death, but that same government refuses to identify the names of the Gardner heist robbers, whom they now claim are dead,

close to four decades later.

In retirement, former FBI lead investigator Geoff Kelly makes the childish claim that the two thieves were George Reissfelder and Leonard DiMuzio, after clumsily hinting

those names for over ten years in a way that was an embarrassment to the city and to the profession of journalism, and should have been to the FBI and to Kelly himself.

In addition, Kelly also now claims that the guard who let the thieves in, Rick Abath, was involved, now that he's safely dead, after saying he was not a suspect for over twenty years,

and says he bases that conclusion on information

that was known the first week. The fact that no one went into the Blue Room, where Manet's Chez Tortoni was taken, after Rick Abath had been in there doing his security rounds,

before the thieves

entered the building, as if there aren't a dozen other convincing reasons to suspect Abath.

In 2013, the FBI said they knew who the thieves were, but now twelve years later and with Kelly in retirement, the Globe reports that

"after scrutinizing dozens of potential scenarios involving a dizzying array of suspects, Kelly has settled on this theory."

The official narrative is transitioning from knowing who the thieves are, to settling on this theory, without any mention of the fact that

this is yet another change to the official narrative, one more examaple of the Boston Globe's

disinformation hijinks as it relates to the government's official Gardner heist narrative, by one of Kelly's

trusted journalists, Shelley Murphy, who has been a knowing party to the state sponsored deception surrounding this investigation since 1993,

when she described Brian McDevitt as "a Swampscott native" and "a California screen writer."

McDevitt was no more a screen writer than he was one of the Vanderbilts, which he had also claimed in one of his previous cons, when he tried to rob the Hyde Collection (Museum) in Glen Falls, NY.

McDevitt had been on Sixty Minutes ten months earlier, to discuss his suspected involvement in the Gardner heist,

and at that time said he had zero writing credits to his name.

Morley Safer: Have you ever published anything anywhere?

Brian McDevitt: Nope, haven't.

While it is true that McDevitt is a Swampscott native, his last known residence prior to moving to California was 69 Hancock Street, in Boston

three miles from the Gardner Museum, which is where he said he was the night of the robbery, while admitting he had no alibi. They even showed the outside of his Boston

apartment building on 60 Minutes.But the story made no mention of McDevitt having ever lived in Boston.

60 Minutes shot of Brian McDevitt's residence at the time of the robbery, three miles from the Gardner Museum

60 Minutes shot of Brian McDevitt's residence at the time of the robbery, three miles from the Gardner Museum

The Boston Globe article begins by stating that McDevitt was "once eyed," as a Gardner heist suspect. "Once eyed," does that mean he was cleared?

He was being brought in front of a grand jury, which seems more like

McDEvitt was still "eyed."

"[UNAMED] Sources familiar with the case confirmed

that McDevitt is not a suspect. They said he was called before a grand jury because he was evasive when interviewed on two occasions by FBI agents,

who have focused on more than a dozen suspects worldwide during the probe which has yielded few clues."

They had focused on more than a dozen suspects, but

none of those suspects were brought before a grand jury. Only a guy, who lived nearby, who tried to rob a different art museum, in a very similar way,

who was under FBI surveillance, and does not have an alibi, and who was not a suspect, but merely evasive when questioned by the FBI,

was brought before a grand jury. Uh huh.

Ten months earlier on 60 Minutes, McDevitt said:

"Down here in the canyon, if you're lucky, you can see the FBI agents who keep watch on my house all the time. They're right down there." And Morley Safer reported

that "The FBI continues to press McDevitt."

But unamed sources confirmed McDevitt is not a suspect. Confirmed is an inside-journalism word favored by Gardner heist dissemblers like Murphy and Kurkjian to bolster their false narrative.

The unnamed sources did not merely say he was not a suspect, they "confirmed"it.

31 years later Murphy was still covering the Gardner heist with a front page story about Anthony Amore's uncorroborated claim about all the leads that are pouring in, this time

from people who have seen the the stolen Gardner art in online Zillow real estate ads. By this time McDevitt's name has been dispensed with at the Boston Globe.

Murphy writes: To this day the baffling case remains one of the city’s most enduring mysteries, with countless theories and a dizzying array of suspects that included a Hollywood screenwriter.

"A dizzying array of suspects," like you get out of Putin's Russia.

The Washington Post reported that "The disinformation campaigns now emanating from Russia are of a different breed, said intelligence officials and analysts.

They fling up swarms of falsehoods, concocted theories and red herrings,

intended not so much to persuade people but to bewilder them." And this is exactly what has been going on with the Boston Globe's coverage of the Gardner heist.

Maybe the array of suspects would not be so dizzying if the Boston Globe would just report about them fully and accurately.

As Murphy herself said on Last Seen Podcast Episode 4: "It's frustrating. All these theories are frustrating.

For everything that points toward these particular suspects [George Reissfelder and David Turner] there's something that points away."

If that is indeed the case then these are not "suspects," at all they are individuals who have been cleared by exulpatory evidence, and nobody to get dizzy over.

If they tried doing coverage of a certain Cold War spy as a suspect, we would see how very undizzy people would get in a hurry.

Murphy is the kind of no getter reporter, that deceitful Gardner heist investigators like Geoff Kelly go back to again and again, in 2015 with

a lie-filled article, and

in 2025 with a no quote accusation against Rick Abath, whom he protected for nearly all of the 21 years he was the Gardner heist lead investigator before Abath died,

except when Abath was doing interviews and publishes excerpts of a book about the case in 2013-2015.

Look to Kelly to do another sitdown with Murphy when his deceitful book comes out in March,

pointing the finger at people who are no longer alive to defend themselves, including an honorably discharged Viet Nam era U.S.M.C corporal, Leonard DiMuzio, the victim of a brutal unsolved homicide.

The second priority, that recovery of the art takes a back seat to, is that the federal authorities do not want the original thieves to benefit financially from the return of the art.

"Anyone — except the thieves themselves — is eligible for the reward,"

the Museum has stated many times.

In 2004, ABC News reported that "In 1997, Youngworth claimed he could broker the return of the missing art. But years went by and, he said, returning the stolen art for the $5 million reward, without getting himself or his friends arrested, had proven to be almost impossible."

"Federal prosecutors did not want the thieves to get away with a deal.

"You can't turn your back on a very serious criminal offense, and if you do, you basically give ammunition to other people to steal priceless works of art,"

said Donald Stern, the former U.S. attorney for Massachusetts.

In 2000, the Guardian reported that:

"Many officials at the Gardner museum, and also some officers at the FBI, did favour some form of compromise,

but those higher up in the legal establishment had no desire to send such a message to the criminal fraternity at large.

The attorney general's office in Washington warned against pandering to 'cultural terrorism.'"

Time and again, the FBI has interfered with a return of the art because they do not want a reward paid out to the original thieves, whom they have gone to great pains to not name and

whom they have been claiming since 2015 are dead.

In 2013 they were still quite alive according to the FBI's Richard DesLauriers:

“The FBI believes with a high degree of confidence in the years after theft the art was transported to Connecticut and the Philadelphia region

and some of the art was taken to Philadelphia

[as recently as 2003]

where it was offered for sale by those responsible for theft." "With that confidence, we have identified the thieves, who are [not were]

members of a criminal organization with a base in the mid-Atlantic states and New England." DesLauriers did not simply mispeak, these were words

provided to the media in a written press release.

DesLauriers did not mispeak, the Globe reporters did not mishear, or fail to accurately transcribe DesLauriers' remarks that day.

That statement from the Globe story is exactly the same, word-for-word, as what appeared that day in an FBI press release.

Compared with the local toughs,

whom the FBI have been hinting were responsible since 2013, (and not in the slightest in 2003) Ramsay had far fewer disincentives to pull off such a monumental crime, and fewer reasons

to concern himself with the consequences of getting caught. His possession of the art, and knowledge of the crime, might well strengthen his negotiating position with federal authorities,

since Gardner heist took place at a time when Clyde Lee Conrad's lengthy trial in West Germany was still ongoing. There was no way Ramsay would be arrested during the trial at least.

At the same time, compared with the FBI's local toughs, there were potentially far greater reasons to conceal the identity of the robber, if it was

someone involved in espionage like Ramsay.

In addition to

discrediting him as a witness, against three fellow spies, if he were arrested for the Gardner heist,

the government would also have to explain why they left Ramsay to roam free, when he had implicated himself in espionage,

18 months prior to the Gardner heist.

As a soon-to-be key witness in an espionage trial of an American soldier in a foreign country, Ramsay had a distinct advantage, not enjoyed by other criminals.

An arrest of Ramsay for the Gardner heist, or any serious crime would have made international headlines and would have jeopardized the successful prosecution of Conrad and possibly others.

In a practice which is permitted under German law, Navarro testified under oath at Conrad’s trial, in a West German court, concerning

what Ramsay had told him about the espionage activity

of Conrad, and others as well as his own. No one was more familiar with the entirety of Conrad's espionage operation than Ramsay, except Ramsay himself.

Around that same time, other criminals, who like Ramsay, had entered into a cooperative relationship with the FBI, had exploited their status as witnesses and informants

to commit additional crimes with impunity.

In 1975, a career criminal named Robert “Deuce” Dussault, along with seven other armed men. pulled off Rhode Island’s Bonded Vault heist.

The Bonded Vault was a secret mob bank, inside an old fur storage building in Providence, RI.

One of the largest robberies in US history, the thieves stole an estimated $30 million in cash, gold, and jewelry from safety deposit boxes.

The heist is considered the biggest in the criminal history of the Northeast.

Well into the 1980s, Dussault, who had turned on his fellow gang members and became a star witness against them to save himself,

was being flown back to Providence, RI to testify at the trial of his fellow robbers, from Colorado, where he had been placed

in the federal witness protection program.

During that time, Dussault proceeded to engage in a crime spree in Colorado, that included

armed heists and shootouts, right when federal prosecutors were still depending on his testimony against the people involved in the Bonded Vault robbery.

In a book on the Bonded Vault case, called “The Last Good Heist,” the authors wrote that “even after all these years, it’s still unclear just how far federal investigators went

to protect Dussault [from arrest and prosecution].”

WPRI-TV investigative reporter Tim White one of the co-authors of the book, said in an interview on Rhode Island’s NPR affiliate, WNPN, that

Robert Dussault "robbed banks and businesses absolutely blind while under the thumb of the federal government."

“Deuce’s now unclassified FBI file shows him escaping from a state prison in Colorado on October 28, 1985; twenty one days later he was robbing a bank there.

How many other robberies he may have committed that year state and federal authorities are either unable or unwilling to say,” the book states.

Another famous example from that same era as the Gardner heist was James "Whitey" Bulger, who “rose to power

as a secret informant

to the FBI and relied on FBI agents to help him get away with murder and extortion.” At the same time “Bulger was credited inside the Justice Department with helping take out the top and middle tier of the local Mafia.”

As William Youngworth, who famously tried to negotiate the return of some of the Gardner art said in the 2005 Gardner heist documentary, Stolen:

"The FBI takes this public posture that 'listen we just want the stuff back and we don't really care how it comes back.' That's not true.

I mean I have sat there behind closed doors and they only have one agenda, the only thing they want is names," and "they want an informant,

more than they want the art back." adding, "They give people passes for 19 murders, you know, we're only talking about some pictures here."

In the same documentary, U.S. Attorney Michael Sullivan asks: "What's more important, the artwork or a criminal prosecution?” If there was any criminal prosecution

that was more important to the U.S. Government, at the time of the Gardner heist, than “some pictures here,”

it was that of the retired U.S. Army Sergeant Clyde Lee Conrad, on trial for espionage, which was taking place right then in a West German courtroom.

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Five)

|

By Kerry Joyce